-

The Islamic Golden Age, roughly spanning the 8th to 13th centuries, witnessed a remarkable flourishing of Islamic civilization. Centres of learning like Baghdad and Cordoba thrived, attracting scholars from across the globe. Significant advancements were made in fields such as mathematics, astronomy, and medicine, laying the foundation for future scientific progress.

-

The European Renaissance served as a crucial foundation for the development of modern science. However, it’s important to acknowledge that the intellectual advancements of the Islamic world significantly influenced the Renaissance itself. Without the contributions of Islamic science and philosophy, the Renaissance, and consequently, modern science, might not have taken the same shape.

-

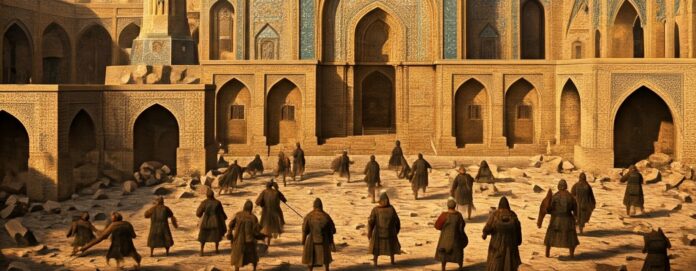

This golden era was abruptly ended in 1258 by the devastating Mongol invasion led by Hulegu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan.

The period preceding the Mongol invasion witnessed a remarkable flowering of intellectual life across the Muslim world. Baghdad, under the Abbasid Caliphate, emerged as a vibrant hub of learning, boasting institutions like the renowned House of Wisdom, a centre dedicated to translation and scholarly inquiry.

During the Golden Age, major Islamic cities, including Baghdad, Cairo, Damascus, Bukhara, and Córdoba, blossomed into vibrant intellectual hubs, renowned for their pioneering work in science, philosophy, medicine, and education.

This era witnessed the brilliance of scholars like Ibn Sina (Avicenna), a polymath whose ‘The Canon of Medicine’ revolutionized medical thought, and Al-Khwarizmi, the father of algebra, whose treatise on ‘ The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing ‘ introduced the concept of algorithms that underpin modern mathematics.

Other notable figures include Al-Biruni, a renowned astronomer and historian, and Ibn al-Haytham, a pioneer in optics whose insights into light and vision profoundly influenced later scientists such as Kepler. This era witnessed a remarkable blossoming of knowledge across diverse disciplines, encompassing mathematics, astronomy, medicine, philosophy, and literature. These intellectual achievements laid the groundwork for many of the scientific discoveries that have shaped our modern world.

The Mongol invasions, spanning the 13th century, inflicted devastating blows upon the intellectual life of the Muslim world. While not entirely extinguished, the vibrant intellectual traditions of this era were severely curtailed. The sacking of major cities, most notably Baghdad, witnessed the catastrophic destruction of renowned libraries like the House of Wisdom, resulting in the irrevocable loss of countless irreplaceable texts. The tragic loss of scholars and intellectuals further exacerbated this intellectual decline, disrupting the continuity of learning and hindering the development of future generations. The destruction of educational institutions like madrasas compounded this crisis, severely impeding the transmission of knowledge and the cultivation of new intellectual pursuits.

The Mongol invasions, driven by a thirst for vengeance against the Khwarazmian Empire, proved catastrophic. The Khwarazmians, by executing Mongol envoys and attacking caravans, had ignited Genghis Khan’s wrath. This act of aggression unleashed a devastating torrent of violence, ultimately leading to the collapse of the Khwarazmian Empire and plunging the region into chaos.

While factors such as political unification and the pursuit of economic expansion undoubtedly played a role, the pivotal event that truly ignited the Mongol conquests on a grand scale was the conflict with the Khwarazmian Empire.

Muslim societies suffered a significant decline in intellectual and cultural pursuits following periods of upheaval. Centres of learning and scientific research were severely damaged, while many Muslims were economically subjugated, relegated to less prominent roles within society.

The rise of the Ottoman Empire, while a period of renewed Muslim power and influence, could not fully restore the pre-Mongol era of Islamic dominance.

Certainly, let’s examine some of the major cities, and their significance, that tragically fell victim to the Mongol onslaught. This list, however, merely scratches the surface of the devastation wrought.

Baghdad, 1258AD

Prior to the Mongol onslaught of 1258, Baghdad stood as a vibrant metropolis and the fulcrum of the Abbasid Caliphate, a zenith in Islamic civilization. The city was renowned as a beacon of learning, attracting scholars and intellectuals from the far corners of the globe.

Academic Importance:

Baghdad boasted a wealth of esteemed institutions of higher education, most notably the Nizamiyah, a renowned university established by the Seljuk vizier, Nizam al-Mulk. These institutions encompassed a diverse curriculum, ranging from theology and jurisprudence to medicine, astronomy, and philosophy.

Libraries and Colleges:

The city boasted a vast network of libraries, the most celebrated being the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma), founded by the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid. This institution housed a voluminous collection of books and manuscripts, numerous of which were translated from Greek, Persian, and other tongues.

Prominent Intellectuals:

- Averroes (1126–1198)—born in Islamic Iberia (modern day Spain), he was a Muslim philosopher who was famous for his commentary on Aristotle

- Avicenna (980–1037)—Persian philosopher and physician famous for writing The Canon of Medicine, the prevailing medical text in the Islamic World and Europe until the 19th century[9]

- Al-Ghazali (1058–1111)—Persian theologian who was the author of The Incoherence of the Philosophers, which challenged the philosophers who favored Aristotelianism

- Muhammad al-Idrisi (1099–1169)—Arab geographer who worked under Roger II of Sicily and contributed to the Map of the World

- Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (d. 850)—Persian polymath head of the House of Wisdom, founder of Algebra, the word “algorithm” was named after him.

- Al-Kindi (d. 873)—considered to be among the first Arab philosophers, he combined the ideology of Aristotle and Plato

- Al-Jahiz (781–861)—author and biologist known for Kitāb al-Hayawān and numerous literary works

- Ismail al-Jazari (1136–1206)—physicist and engineer who is best known for his work in writing The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices in 1206

- Omar Khayyam (1048–1131)—Persian poet, mathematician, and astronomer most famous for his solution of cubic equations

These individuals, amongst many others, made substantial contributions to the intellectual and cultural flourishing of the Islamic world.

Aleppo 1260AD:

Prior to the Mongol invasions, Aleppo flourished as a metropolis, celebrated for its intellectual vigour and economic prominence. It boasted numerous libraries, colleges, and a rich intellectual heritage.

Academic Importance:

Aleppo served as a prominent center of Islamic learning, attracting scholars from across the region. The city was home to several renowned educational institutions, including the Nizamiyya of Aleppo, a prestigious madrasa (religious school) established by the Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk. These institutions offered instruction in various disciplines, including Islamic law, theology, philosophy, medicine, and astronomy.

Libraries and Colleges:

While the exact number of libraries and colleges in Aleppo before the Mongol invasions is uncertain, historical accounts suggest that the city possessed a considerable number of these institutions. The Nizamiyya of Aleppo, for instance, housed a substantial library containing a vast collection of books and manuscripts. Other notable educational institutions included the Umayyad Mosque, which also functioned as a center of learning, and various private libraries belonging to wealthy patrons and scholars.

Prominent Intellectuals:

Aleppo produced numerous prominent intellectuals who contributed significantly to various fields of knowledge. Some of the notable scholars associated with the city include:

- Al-Farabi (Damascus 950-51): Ruler Sayf al-Dawla graciously provided al-Farabi, renowned in the West as Alpharabius, with a residence in Aleppo. Born near Farab in Turkestan to a Turkish family, Abu Nasr Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn Tarkhan ibn Uzlagh al-Farabi, a scholar of immense significance, pursued his studies in Baghdad. He achieved his greatest prominence in Aleppo before his passing in Damascus circa 950-51 at the approximate age of 80.

- Djamal Eddin Ibn Al-Qifti (d. 1248): Born in Egypt in 1172, he was taken to Cairo by his father at an early age to receive an education in reading and writing. Subsequently, he departed from Cairo for Jerusalem and ultimately settled in Aleppo, where he resided for the remainder of his life.

- Kamal Eddin Ibn al-Adim (d. 1262): He stands as the preeminent historian of his native Aleppo, his renown primarily stemming from his monumental biographical work, Bughyat al-Talab (The Student’s Desire).

- Ibn Taymiyyah (1263-1328, Damascus): A prominent theologian and jurist who played a crucial role in the development of Hanbali jurisprudence.

- Ibn al-Qayyim al-Jawziyyah (1292-1350, Damascus): A disciple of Ibn Taymiyyah, he was a prolific writer on various Islamic sciences, including theology, jurisprudence, and Sufism.

These scholars and many others contributed to the intellectual and cultural richness of Aleppo, making it a vital center of Islamic learning and scholarship.

Bukhara, 1220AD

Bukhara: A Jewel of Islamic Scholarship Before the Mongols

Before the Mongol invasions, Bukhara stood as a beacon of Islamic scholarship, rivaling even Baghdad in its intellectual vibrancy. Nestled in present-day Uzbekistan, the city boasted a rich tapestry of educational institutions, libraries overflowing with knowledge, and a constellation of brilliant minds.

Academic Eminence:

Bukhara’s allure lay in its strategic location along the Silk Road, making it a crossroads for trade, ideas, and cultures. This confluence fostered a dynamic intellectual environment where scholars from across the Islamic world converged to study, debate, and contribute to the vast corpus of Islamic knowledge. The city’s madrasas, or religious schools, were renowned for their rigorous curricula, attracting students eager to delve into Islamic law, theology, philosophy, and the sciences.

A City of Libraries:

Bukhara was home to numerous libraries, each a treasure trove of manuscripts and books. The most famous among these was the Mir ‘Arab Madrasa library, which housed an extensive collection of Islamic texts, including works on astronomy, medicine, mathematics, and literature. These libraries served as vital repositories of knowledge, preserving the intellectual heritage of the Islamic world and providing scholars with access to a wealth of information.

Prominent Intellectuals:

A millennium ago, Bukhara stood as one of the foremost intellectual and religious centres within the Islamic world, rivalling the eminence of Baghdad and Cairo. Scholars and students, drawn from the length and breadth of the Silk Road and beyond, flocked to Bukharara’s madrassas. Amongst these luminaries were some of the most illustrious figures of the Islamic Golden Age: Imam Al-Bukhari, Abu Ali ibn Sina (Avicenna) and his mentor al-Qumri, Sadiduddin Muhammad Aufi, Bahauddin Naqshband, and Amir Kulal (Shams ud-Din). Their presence was fostered by the generous patronage extended by successive rulers, the existence of vast libraries overflowing with priceless manuscripts and books.

- Abu Nasr al-Farabi (died in Damascus): A philosopher and polymath known for his work on logic, metaphysics, and political philosophy. His commentaries on Aristotle’s works were highly influential in the Islamic world.

- Abu Rayhan Biruni (Khwarazm): A renowned scientist and polymath who made significant contributions to astronomy, geography, and history. His works on Indian culture and civilization remain invaluable sources of information.

- Ibn Sina (Also in Ray): A polymath who made significant contributions to philosophy, medicine, and science.

These scholars, along with many others, transformed Bukhara into a center of intellectual excellence, attracting students and scholars from far and wide. The city’s vibrant intellectual life was a testament to the flourishing of Islamic civilization during this period.

However, in 1220, Genghis Khan’s forces laid siege to Bukhara, resulting in the destruction of much of the city and the massacre of its inhabitants. The city’s libraries were ransacked, and many of its scholars were killed or dispersed, plunging Bukhara into a period of decline.

Despite this devastating blow, Bukhara eventually recovered and regained some of its former glory. However, the Mongol invasions left an indelible mark on the city, and its intellectual prominence never fully recovered.

Samarkand, 1220AD

Samarkand, situated on the Silk Road, was a thriving hub of trade and intellectual activity before the Mongol invasions. The city boasted a rich history dating back to the Achaemenid Empire, and its strategic location facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures.

Academically, Samarkand was a prominent center of learning, with numerous institutions dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge. The city was home to several renowned libraries, including the Ulugh Beg Observatory Library, which housed a vast collection of astronomical texts and instruments. These libraries served as repositories of knowledge, attracting scholars from across the region.

The city also housed numerous colleges, known as madrasas, where students studied various disciplines, including Islamic law, theology, philosophy, and medicine.

Prominent intellectuals who resided in or were associated with Samarkand include:

- Ulugh Beg: A Timurid prince and a renowned astronomer, mathematician, and historian. He established the Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand, which made significant contributions to astronomy.

- Al-Biruni (Khwarazm): A scholar who excelled in various fields, including astronomy, geography, and history.

- Abu Mansur al-Maturidi: A prominent theologian who developed the Maturidi school of Sunni Islam, a major theological tradition that continues to influence Islamic thought today.

- Jamshid al-Kashi (c. 1380 – 1436): a renowned mathematician and astronomer, lived and worked in Samarkand, now located in Uzbekistan.

- Qadi Zada al-Rumi: (more accurately known as Salah al-Din Musa Pasha) was born in Bursa, Turkey, in 1364 and passed away in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, in 1440 C.E.

These scholars and institutions contributed to Samarkand’s reputation as a center of intellectual excellence, attracting scholars and students from across the Islamic world. The city’s rich intellectual heritage, however, was tragically disrupted by the Mongol invasions, which resulted in the destruction of numerous libraries, the deaths of many scholars, and the dispersal of valuable intellectual resources.

Herat, 1221AD

Herat, a city in present-day western Afghanistan, was a prominent center of learning and culture in the Islamic world before the Mongol invasions. It boasted a rich intellectual tradition, with numerous libraries, colleges, and renowned scholars contributing to various fields of knowledge.

Academic Importance:

Herat’s strategic location on major trade routes, including the Silk Road, facilitated the exchange of ideas and goods, contributing to its intellectual vibrancy. The city was home to several renowned educational institutions, including the Nizamiyya of Herat, a prominent madrasa (religious school) that attracted scholars from across the region. These institutions offered instruction in various disciplines, such as theology, law, medicine, astronomy, and philosophy.

Libraries and Colleges:

Herat possessed a rich collection of libraries, some of which were attached to madrasas or mosques. These libraries housed a vast array of books and manuscripts on diverse subjects, including Islamic sciences, literature, history, and philosophy. The exact number of libraries and colleges in Herat before the Mongol invasions is difficult to ascertain, but historical accounts suggest that the city had a thriving intellectual ecosystem.

Impact of Mongol Invasions:

The Mongol invasions of the 13th century had a devastating impact on Herat, destroying much of its infrastructure, including libraries and colleges. The city’s intellectual life was disrupted, and many scholars were killed or forced to flee.

It is important to note that historical records about Herat before the Mongol invasions are limited. However, the available evidence suggests that the city was a significant center of intellectual activity, contributing to the rich cultural heritage of the Islamic world.

Other prominent cities destroyed by Mongols, which housed thousands of Islamic scholars and researchers and a huge number of books and manuscripts:

1220AD Askhabad, 1252AD Astrakhan, 1240AD Aleppo, 1238AD Arabil , 1232AD Amol, 1228AD Ardahan,1258AD Baghdad, 1232AD Bokhara, 1256AD Baku, 1221AD Bamyan, 1230AD Bilecik, 1243AD Dashonwiz, 1237AD Erzincan, 1221AD Herat, 1223AD Isfahan, 1234AD Izmit,1222AD Jalalabad, 1242AD Konya, 1221AD Kabul, 1221AD Kandahar, 1230AD Kayseri, 1228AD Mianeh, 1219AD Merv, 1237AD Mosul, 1220AD Nishapur, 1235AD Osh, 1230AD Qazvin, 1225AD Rasht, 1232AD Samarkhand, 1235AD Samara, 1235AD Sokhumi, 1234AD Sanandaj, 1234AD Sivas, 1223AD Tehran, 1221AD Tabriz, 1224AD Tiblisi, 1229AD Turkmonabad, 1227AD Urganch, 1227AD Urmia, 1230AD Usak

The End of an Era:

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of unparalleled intellectual and cultural achievements, driven by the Abbasid Caliphate’s emphasis on knowledge and learning. However, the Mongol invasions in the 13th century brought this era to a catastrophic end, with the destruction of key cities like Baghdad. The loss of these cultural and educational centers had long-lasting impacts on the Islamic world, leading to a shift in the global center of knowledge and a decline in the political and economic power of Islamic societies.

The eminent Islamic historian, Ibn al-Athir, says:

‘For several years, I hesitated to recount this incident, finding it too overwhelming to bear. I kept postponing it, reluctant to dwell upon such a calamity.

He continues, ‘Who could easily write an obituary for Islam and the Muslims? Who could bear to recount such a tragedy? I wish my mother had not given birth to me, and that I had died before this and been forgotten.’

Suhaib Nadvi

[Email: Contact@Laahoot.com]

Laahoot Digest

Let’s connect on Social Media:

https://www.facebook.com/LaahootDigest

https://x.com/LaaHoot

https://www.youtube.com/@LaaHoot