Cristina Puerta

UNESCO

What makes us human

For most people, the terms “sea ice” or “pack ice” are sufficient to designate the expanse of ice formed on the water’s surface. Inhabitants of the Bering Strait and Greenland, however, use nearly 1,500 expressions to evoke the multiple facets of this phenomenon. Curious fact aside, if the Inuit-Aleut languages were to disappear, all of the knowledge associated with this terminology would disappear with them, depriving scientists of useful information in this time of climate change.

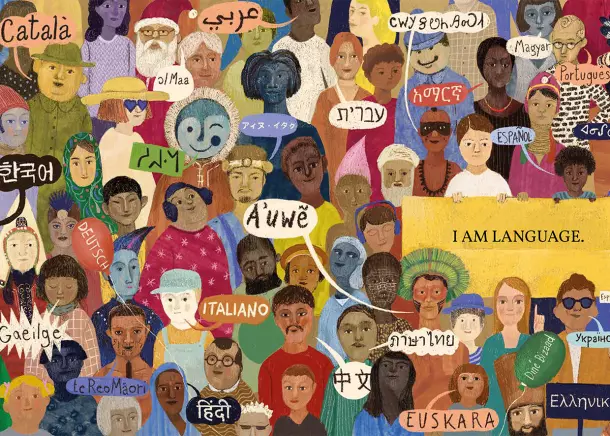

With 40 per cent of the world’s 7,000 living languages at risk of disappearing for lack of speakers by the end of the 21st century, What Makes Us Human, the book by Brazilian linguist Victor D.O. Santos and Italian illustrator Anna Forlati, highlights the importance of language diversity. Before being published in Brazil, it was selected in 2022 by the specialist jury of The Unpublished Picture Book Showcase by dPICTUS (which showcases some of the best picture books yet to be published) and the prestigious International Youth Library in 2023.

What’s in a name?

The question Juliet asks herself when she learns that Romeo is a Montague in Shakespeare’s tragedy (“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet”) seems more the stuff of linguistics than of children’s literature. Yet What Makes Us Human demonstrates, in the form of a riddle, that language is an instrument, a human construction to which an infinite number of generations have given form and meaning.

In questioning the nature and function of language, the book is in the same vein as other children’s texts such as Edward Lear’s The Book of Nonsense (1846), What Do You Say, Dear? A book of manners for all occasions by Sesyle Joslin and Maurice Sendak (1958) or Achimpa by Catarina Sobral (2012).

What Makes Us Human reveals the richness of a multilingual world, but also its fragility

What Makes Us Human reveals the richness of a multilingual world, but also its fragility. It is thus an essential tool for the International Decade of the World’s Indigenous Languages (2022-2032), which UNESCO is leading with the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs to draw attention to the alarming disappearance of languages and the urgent need to safeguard them.

Committed publishing houses

To promote the Decade, UNESCO is co-publishing monolingual and bilingual versions of What Makes Us Human, in majority languages as well as in regional and indigenous languages (see box). The aim is to preserve a plurilingual and diverse experience of the world. “For as long as humans have existed, they have found a way to communicate with their fellows. The written word, and later books, gave these languages the opportunity to leave their mark, to serve future generations. Now it’s up to us to evolve in the right direction,” explains Simon de Jocas, director of the Canadian publishing house Les 400 Coups.

Children schooled in the language spoken at home have a 30% higher probability of understanding what they read by the end of primary school

This cooperation with UNESCO demonstrates the role publishing houses can play in revitalizing regional and indigenous languages. We now know that children schooled in the language spoken at home are 30 per cent more likely to understand what they read by the end of primary school, and they have better social skills. This is why UNESCO celebrates International Mother Language Day on 21 February, calling on governments to promote multilingual education in the early years of schooling.

“Create a reading public”

In countries heeding the call, a new market for school texts and children’s literature is developing. Such is the case in sub-Saharan Africa, where the challenges of the emerging market are widely debated. While some believe that books in local languages should reflect their traditions, others see these languages as bridges to other cultures. That is the opinion of Edwige-Renée Dro, an Ivorian author and bookseller, who describes the challenge as follows: “Now we have to create a reading public.”

Here is also an opportunity to unite the players in the publishing chain around a single project: accepting our own indigenous heritage, and not perpetuating colonial reflexes, its isolation and disappearance. Publishing houses have the creativity and energy;